- Home

- Chelsey Philpot

Be Good Be Real Be Crazy Page 9

Be Good Be Real Be Crazy Read online

Page 9

“Wow,” said Einstein. “You’re even more socially awkward than I am.”

Young Otis considered this for a moment before dropping his arm and shrugging in a what-can-you-do? gesture. “I’ve been homeschooled since I was eight and working here since I turned fourteen. To quote the great Apollo Aces, ‘The universe is stacked against me. I’ve been down to up from the—’”

“‘Start. Time will tell if it’s all been worth it. Livin’s its own kind of art.’” Einstein’s voice cracked on “been worth it,” but he was too in awe to try covering it with a cough like he usually did. “That’s the third-best song on the album.”

Young Otis bounced with excitement as he spoke. “Every time I go with my mom to the mall, I sneak into the music store and listen to ‘Last Song of Our Lives’ like a billion times. I can pretty much recite the whole album.”

“That is awesome.” Einstein shook his head as he scooped up the napkins at his feet and dumped them in a trash can next to the sunken picnic table. “Gross! Why do you have to listen at the mall?” Someone had written “O tush Sucks” in green spray paint around the bottom of the can.

Young Otis tapped a crushed soda can with the toe of his sneaker. “My parents are kind of strict.” He looked up from the asphalt. “Which is why I really, really, really need to go with you guys. I don’t even care where.”

The driver’s-side door swung open and Mia’s face appeared over the Banana’s roof. “Won’t your parents be worried?”

“They’re at a conference in Nevada. And my grandma says I need to get out more. You can even ask her. Wait. One second.” Young Otis dropped his backpack on the ground, stuck his arm in practically up to his shoulder, and started digging. He didn’t seem to notice or care that a pair of jeans, two comic books, and a bunch of other knickknacks spilled onto the pavement as he hunted. “Aha! Got it,” he said, holding a large cell phone above his head like it was an Olympic medal. “One sec.”

Young Otis jabbed his finger against the screen, then held the phone to his ear, smiling hugely the entire time. “It takes her a while to press the answer button,” he whispered, covering the bottom half of the phone with his free hand. “Naniji?” he said, pulling his hand away and holding a finger up. “No, no. I have a question.”

While Young Otis paced and talked, Homer dumped his napkins in the “O tush Sucks” trash can. He stood by Einstein and watched Young Otis pace, turn, kick at trash, and then nod vigorously before sprinting around the Banana and shoving the phone at Mia.

“My grandma wants to talk to you because she thinks pregnant ladies are more responsible and less likely to be serial killers.”

“Oh, that makes sense,” Mia said brightly before taking the phone. “Hello?”

Young Otis shambled next to Einstein and Homer, all three of them listening to the few words Mia got in.

“Sure. Okay. Uh-huh. Yes. Very safe. I’m not sure. Let me ask.” Mia put the phone against her chest. “Homer, Otis’s grandma wants to know if you’ve ever gotten a traffic violation.”

“Not even a parking ticket,” Einstein shouted before Homer could open his mouth.

Mia nodded and held the phone back to her ear. “No, ma’am. Not even a parking ticket. Okay. Okay. Twice a day? I’ll let him know. Okeydokey. Bye-bye.” Mia hung up and turned toward where the three guys were standing in line in front of the sunken table. “Done and done.” She knocked her knuckles against the Banana’s roof three times. “You just need to be back before your parents are and call Grandma twice a day.”

“That easy?” Homer said, looking first at Mia, then at a beaming Young Otis. “Just like that? Your grandmother?”

Young Otis shrugged. “Like I said, she’s extremely worried about my—and this is how she puts it—‘real life skills.’ Plus, this way she gets to watch all the American shows she doesn’t get in India without any interruptions.”

“Why do you want to go so badly?” Mia asked kindly as she stepped around the open door and handed Young Otis his phone.

“Thanks.” Young Otis slid the phone into a front pocket. “You guys are like the first people under fifty to ever stop here, and I’ve never been outside of Delaware.” He straightened his shoulders. “I’ll be super quiet. I’m only fourteen, so I don’t have my license, but I know a few things about cars.”

“How do you know about cars?” Einstein was digging around on the floor of the backseat. “Aha!” He held a travel-size bottle of hand sanitizer over his head. “Today, the Earth. Tomorrow, the Galaxy.” Whatever voice Einstein was trying to mimic, Homer thought he sounded more like Darth Vader before puberty than a video game hero.

“You like Apollo Aces and you play Future Space 3000?” Young Otis’s expression was a mixture of awe and disbelief.

“Before we stopped here, I was practically going to beat level eight,” Einstein replied, crossing his arms and dipping a shoulder. “I’d just gotten to the part—”

“Wait, back to the question. How do you know anything about cars?” Homer wanted to stop the gaming geek-out before it gained momentum. “No offense, but you seem kind of . . .” He struggled to find the nicest way to put it. “Sheltered.”

Young Otis kicked a loose chunk of asphalt. It skittered a few feet before getting stuck in a pothole. “If I finish lessons early, I get out of ‘school’”—he made air quotes while he said “school”—“early. The only places with people around in my neighborhood during the week are the bank, the nail place, and Arnie’s Automotive. Arnie lets me hang out if I don’t lean on the tire piles.”

“You can come.” Einstein pointed to the passenger side of the backseat. “You’re over there. I’m always behind Mia. Her legs are shorter.”

“Awesome.” Young Otis yanked the back door open and threw himself on the seat.

He slammed the door shut as Mia slid back into the driver’s seat. “Are you okay? That landing sounded like it hurt.”

Homer waited until Mia shut her own door to speak. “Really, Steiner?”

“What?” said Einstein. “I feel bad for the guy. Besides, if the world ends December twentieth, don’t you want to go knowing that you did something nice for a stranger?”

Einstein stuck his hands on his hips in such a way that he could have been a smaller version of D.B. A wave of homesickness hit Homer so suddenly and powerfully that he felt his eyes sting. “The world’s not . . . whatever. He’s your responsibility.” Homer pretended to scratch his forehead so he could wipe his face before getting in the car. He had to yank on the passenger-side door three times to get it open.

Einstein whistled as he tugged at his own door. “Otis, what’s your real name?”

“Siddhartha Samir Sahota, but you can call me Sid.”

“So, Sid.” Mia pumped the gas pedal until the Banana’s engine caught. “Tell us about yourself.”

Sid started talking as Mia pulled out of the Otis Amos Chester Memorial Rest Stop and Museum parking lot and didn’t stop until she took a sharp left turn into the Time in a Bottle Inn in New Valor, New Jersey.

For a guy who had never been anywhere, Sid had an awful lot to say.

THE PARABLE OF THE NEVER BEEN ANYWHERE GUY AND THE FOUR MIRACLES

YOU CAN’T BLAME HIS PARENTS for being overprotective. After all, it was due to a series of miracles that the Never Been Anywhere Guy existed at all.

His parents met when they were not quite old, but definitely no longer young. Dr. Amanpreet Sahota was a tenured professor of religion with a large, dusty office where stacks of books sprouted like weeds, pens and student papers disappeared for years, and his computer wheezed like an asthmatic old man. Dr. Bhavjeet Batra was an art historian who specialized in the restoration of medieval tapestries, an esoteric occupation that demanded solitary days in museum basements, international travel, and fluency in three languages.

As brilliant as they were, neither one had realized the depth of his or her individual loneliness until they didn’t have to be alone anymore. That b

oth doctors were attendees at separate conferences in the same hotel in Boringville, Wyoming, and that both made the uncharacteristically impulsive decision to take a late-night swim in the indoor pool was Miracle Number One.

Miracle Number Two was that the Never Been Anywhere Guy was concocted with a mixture of science, hope, and a great deal of luck. Dr. Sahota and Dr. Batra tried the old-fashioned way to have a child. (For the record, the Never Been Anywhere Guy thought this was disgusting, and he would much prefer that his parents skip this part in the retelling of Miracle Number Two.) Then they tried shots. That was painful. Then they decided to adopt. That was frustration, forms, and red tape. Then, just as they were ready to give up completely, Dr. Batra said to Dr. Sahota, “A baby in a lab? It’s a long shot. But we might as well try.” Their test-tube baby was born with hair so black it looked purple under the hospital’s bright lights.

Miracle Number Three happened when the Never Been Anywhere Guy was eight and he fell out of a tree. Until that day, he’d had a regular-ish childhood. Sure, his parents were higher strung than most and he couldn’t eat sugar, gluten, or anything not organic. But he went to school, read comics, played soccer, and was generally kind of normal. However, when he woke up in the hospital—the fall had knocked him out—everything had changed. Seeing their son lying on the grass, unconscious, had snapped something in both Dr. Sahota and Dr. Batra.

The Never Been Anywhere Guy was homeschooled from that point on. He wasn’t allowed to play sports, date, or travel on germ-ridden public transportation. Even though all his grandparents were in their seventies, they were the ones to make the twenty-hour flight to Delaware from New Delhi instead of him going to them. And after the first time his cousins came to visit, Auntie Ujala called to complain that the little ones were walking around with thermometers in their mouths and telling other children on their street that that was what all American kids did.

The Never Been Anywhere Guy grew up to be a restless fourteen-year-old who was desperate to go somewhere, everywhere, anywhere. Maybe it was the scratchy beard and leather pants he had to wear for the job his parents had lined up for him, a job he hated. Or maybe it was something larger. Maybe seeing three kids who looked around his age spill out of an ugly yellow sedan was the tipping point, the final push he needed to tighten the mishmash of seclusion, curiosity, and boredom inside him into an unbearable ball studded with broken bits. Suddenly, he knew that he had to go and this might be his only chance.

That the three strangers agreed to take him became Miracle Number Four.

THE INN WHERE TIME STOPPED AND BEGAN

“SHOOT.” HOMER TRIPPED OVER a wrinkle in the mud-colored carpet for the second time since he, Einstein, and Sid had entered room 117 at the Time in a Bottle Inn. With this stumble, instead of falling face-first onto one of the double beds, he sent his cell phone flying across the room and had to reach behind a scratched nightstand to retrieve it.

“D.B., you there? Yeah. Sorry. This room is trying to kill me.” To be safe, Homer decided to move his pacing to the worn patch of linoleum in front of the bathroom.

“Yeah,” he said. “It’s actually not the worst place we’ve stayed in.” Homer was too tired to recount Einstein’s detailed description of the swampy smell of the bedspreads and the look on Sid’s face when he slid off the bed closest to the door and found a dirty sock and a sticky mug underneath.

“Uh-huh. No, like I said, Sid’s really nice. Yeah, he’s amazed by everything. I doubt that he’s ever slept in a scuzzy hotel. He got way too excited about the free soap. He thinks Einstein is the coolest guy in the world, so that’s something.” Homer caught a glimpse of himself in the bathroom mirror. Just enough to make him pause and stare back at the guy with a phone pressed to his ear. His hair was the longest it’d been since he was a little kid. When he ran his hand over his head, he looked like a blond porcupine.

“What do you mean? Like, what we’ve seen on purpose or just in general?” Homer hated this question. It was so simple, but when D.B. asked it each night, he struggled to answer. How could he possibly condense all the small, epic, weird, funny, and bizarre things that he’d seen into a few sentences? Out loud, he gave D.B. a vague rundown, while somewhere else in his brain he tried to take stock. That day alone, they’d stopped at six different gas stations, eaten at four different fast-food places, spotted two abandoned sofas by the side of the highway, and driven by more roadkill than anyone should have to see in a lifetime.

They’d passed a scarecrow in a tuxedo, a rusted swing set lying on its side under an overpass, and a child’s dress shoe with frayed black laces that swung side to side like a waving hand. He could tell D.B. about all these things, but explaining how each one of them was so much bigger than what he was saying felt impossible, so he changed the topic instead.

“Have you heard anything from Chief Harvey about the lot?”

The knock at the door couldn’t have come at a better time as far as Homer was concerned. “Wait a second, I think Einstein and Sid lost their key card. Uh-huh. No, just the vending machines. Sid eats nonstop.” He pulled the door open harder than he meant to. “Oh, hey.”

Mia had changed into pajamas that were long enough to cover her bare feet right to the toes and a green sweatshirt that fell a few inches above her knees. Her hair was piled on top of her head in a way that cast half her face in shadow. She looked so obliviously beautiful, Homer felt like he’d been punched.

Mia’s surprised expression turned into an apology when she saw that Homer had his phone pressed to his ear. “I’m so sorry. I’ll come back. In the morning.”

“Wait,” Homer called, but Mia had already started walking away. “No, sorry, D.B. I was talking to Mia. What? Good. Yeah. Happy. Listen, I’m going to go. Steiner has his phone on him. No, if you call enough times he’ll pick up. Yup. Yup. Love you, too.”

Homer slid his phone into his pocket, and then a key card. He tried to get his hair to lie flat but gave up after just a few swipes. He pulled the door shut behind him with a click, padded down the springy and surprisingly clean hall carpet to Mia’s room five doors down, and knocked

Mia opened her door slowly. “Hey. I’m sorry. You didn’t need to stop talking.”

Suddenly, Homer didn’t know where to look. Meeting Mia’s eyes seemed too intense, but staring over her would be rude. He settled for looking down at his shoes and her feet. The pink polish on Mia’s toenails was chipped and the ink tattoo she’d doodled on the bridge of her right foot that morning had already faded. An awkward amount of time passed before Homer could get his brain to stop racing and his mouth to respond. “No worries. D.B. would have kept me on the phone for hours, so I should be thanking you for saving me.”

Mia smiled and tried to wipe flyaway strands of hair off her face. “Long hair is so annoying.” She caught a few strands and tucked them behind one ear just as others drifted free. “Do you want to come in?” She opened the door wider.

“Yeah, sure.” As Homer walked by Mia, he stretched out his hand, and, without realizing what he was doing, he brushed the newly loose strands behind her right ear. “It’s hard to get it all without a mirror. Not that I know, but I imagine it’s hard.” He dropped his hand. Cleared his throat and silently prayed that the light in Mia’s room was as terrible as the light in his.

“My hair is easy. It’s stuff like reaching behind me or painting my toes that’s near impossible. Now that I’ve got to work around the watermelon in front of me.” Mia shut the door and hopped onto the bed, folding her legs to the side.

Homer sat down in an office chair by the window, catching his feet against the desk to keep from spinning. “When you jump around like that, it’s easy to forget you’re pregnant.”

“True story: I sometimes forget, too.” Mia shifted backward until she was leaning against the headboard. “Not a lot, but sometimes. It’s funny.” She yanked the elastic out of her hair, put it between her teeth, and gathered the waves of red back on the top of her head as she spo

ke. “I fwought I’d be terrify but I rembwer and”—she grabbed the elastic with one hand and twisted her hair until she once again had a messy bun—“it makes me happy.”

“Do girls know how amazing it is when they do that?” Homer asked. “It’s like you’re all secret hair ninjas. Swoop, swoop, twist, and done.”

“Ha.” Mia giggled and chucked a striped throw pillow at Homer, who caught it and stuck it behind him.

“Thanks. I needed lower back support.” He put his feet up on the desk, his hands behind his head, and leaned back like he was in a beach chair.

“Homer, do you think I’ll be a good mom?” Mia looked down at her hands, twirling the large silver ring she wore on her right pointer finger.

Homer dropped his feet to the floor. “That came out of nowhere. Of course I do. You’re going to be a great mom.”

“Why?” Mia looked up, and even in the crappy light from the crappy lamps, Homer could see that she was biting the sides of her mouth, trying not to cry. “How do you know?”

“Because you’re kind and thoughtful and really, really patient.” Homer tapped his knuckles against the office chair’s armrests. “You’re pretty much the only person in the world who Einstein hasn’t lost his marbles with. And that’s because you listen to him each time as though you haven’t heard his theories a million times before and as though everything he’s saying isn’t outrageous.”

Mia sniffed and then wiped her eyes against her sleeve. “He’s so smart and I want Tadpole to be smart.” Mia dropped her arm and looked down at her hands again. Her voice was scratchy, each word a burr that caught in her throat. “I don’t want him—or her—to be dumb like me. I want better.” Mia’s eyes searched Homer’s face like she was worried about what she’d find. “I’m not asking for Tadpole to be a genius, but I want her, him, to be happy and safe and . . . I don’t want to mess up. I don’t want to be like my mom. And I’m so scared that—” Mia closed her eyes and breathed in and out twice before she opened them. “I need you to know that I don’t feel sorry for myself. Other people have had it way worse than me. I don’t want you to think that—”

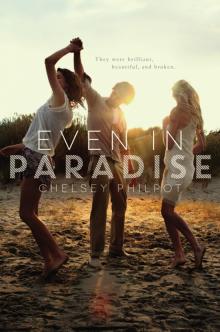

Even in Paradise

Even in Paradise Be Good Be Real Be Crazy

Be Good Be Real Be Crazy