- Home

- Chelsey Philpot

Be Good Be Real Be Crazy Page 7

Be Good Be Real Be Crazy Read online

Page 7

“List?”

“Of things I’m bad at. Lying falls somewhere in between juggling and biology.”

“You’re silly, Homer. You’re great at tons of stuff.” Mia’s pitch rose as she continued. “You’re nice and sweet and tall and good at picking up heavy things. And everyone likes you because you smile with your whole face, not just your mouth.”

Homer pretended to search for a radio station so he wouldn’t be tempted to look over his shoulder. Most of the time it was okay that Mia didn’t like him more than as a friend, but sometimes, when she said stuff like that, a dam inside him threatened to crumble, to flood his chest with a feeling that wasn’t quite sadness but wasn’t quite regret either. It was like experiencing a memory in the present. It took the Banana drifting onto the rumble strip for Homer to snap out of his thoughts.

“Question. What’s the worst thing you’ve ever done?” Mia asked.

“What do you mean?”

“Like, have you robbed a bank?”

“Nope.” Homer put on his blinker and passed the minivan he’d been stuck behind for over an hour. He’d had plenty of time to assemble an image of the family inside from the many stickers lining the van’s rusted bumper: the parents were proud of their honor students, wanted peace for the world and Mick Swanzy for Sheriff, and they loved their dachshund—a lot.

“Have you ever kidnapped anyone?”

“Nope.” Homer felt the corners of his mouth twitch. He could hear the smile in Mia’s voice, and that made it nearly impossible not to smile with her.

“Masterminded the takeover of a politically unstable country?”

“Ha. You’ve been spending too much time with Einstein.”

The backseat crackled as Mia shifted around. “So spill. What’s the worst thing you’ve ever done?”

Homer slid his hands up and down the steering wheel. The view outside had morphed from dense South Carolina woods into never-ending North Carolina fields, scrubby, but still tinted with green even in December. “My dads love to bring up the time I set one of their tea towels on fire in the backyard.”

“What’s a tea towel?”

“It’s a useless piece of fabric that just takes space away from towels that are actually useful.”

“Oh.” Mia frowned. “Is that why you set it on fire? Because you were mad at it?”

“No.” Homer coughed. “It was an accident. I was trying to do a voodoo ceremony and—”

“Why? Were you making a voodoo doll of someone?”

“No. My dads said that I had a stage where I was super into rituals. D.B. was worried I was going to join a cult, but Christian said I was ‘emotionally mature’ and should be ‘encouraged to explore’ my ‘innate spiritual nature.’” Homer laughed. “Or something like that. Then he went to the hardware store and bought me a bunch of battery-powered candles and hid all the matches.”

“Huh.” Mia sat up. Out of the corner of his eye, Homer saw her wrap her arms around her stomach. “You’re lucky,” Mia said quietly. She turned toward a side window. “That Christian and D.B. found you. Got you.”

“Yeah. I know.” Part of him wanted to shout and pound his fists against the steering wheel. Yeah, he was lucky, and yeah, it really sucked that Mia wasn’t. It sucked that she never got a new family. Another part of him wanted to stop the car, pull Mia into a hug, and tell her she was amazing. That any family would have been incredibly lucky to have her. That he was pretty sure, very sure, that he was in love with her. Instead he kept his hands on the wheel, cleared his throat, and hoped that words that made sense would come out of his mouth. “I was a strange little kid.” Homer shook his head. “I guess I still am. Strange, that is.”

“I used to make my stuffed animals pray when I was in fourth grade. Every night before bed, I’d line up Elly Pants, Boo Bear, and Mike.”

“Mike?”

“Mike the Giraffe. I was still living with my bio mom then, but it was around the time her drinking got so, so bad. She yelled a lot. Fought with her boyfriend. I started going to my room earlier and earlier every night, you know, to get out of the way. But I wasn’t tired enough to fall asleep, so I’d set my toys up and pretend they were praying.” Mia laughed. “I didn’t know any real prayers, so I had them recite Christmas carols and then ask God for the stuff I secretly wanted.”

“Let me guess. Mike the Giraffe’s favorite was ‘The Twelve Days of Christmas’?”

“Because of all the animals?” Mia said, reaching down to the floor. When she sat up, she had a pen woven between her fingers.

“Yup.”

“Ha.” Mia put one end of the pen in her mouth. “You’re so clever, Homer.”

“No, I’m not. Glad you’re fooled, though.” Homer felt his cheeks flush. “I’m also not a germ-o-phobe or anything, but it might not be a good idea to put that pen in your mouth.”

“This pen? Why?” Mia kept chewing.

“Because it was on the floor and I don’t think the Banana’s previous owner was concerned about the mats staying clean.”

“Huh.” Mia chomped down twice more before spitting the pen cap into her palm. “Good point.” She dropped the cap and pen on top of a stack of magazines at her feet.

“So, what’d the stuffed animals ask for?”

“Oh, stupid stuff.” Mia made a dismissive motion with her hand.

Homer decided not to press her, but he couldn’t keep himself from asking one more question. “What’s the worst thing you’ve done?”

“Ever?”

“Yup.”

“I stole something.”

“A big something?”

“Yeah. The first time I got to go back and live with my mom, I stole her car keys.”

“Where did you want to go?”

“Oh, no. I didn’t want to drive. I was only fourteen. I did it because I didn’t want my mom to drive. I don’t remember how long it was before she started drinking again, but one night she was loopy and I took her car keys. Whew. She got so, so mad.”

“You were trying to help her,” Homer said lamely.

“Yeah. But then I told Ms. Kincaid, the social worker, about hiding the keys. I thought she’d be happy that my mom couldn’t drive, but instead my mom got in trouble and Ms. Kincaid said I had to live somewhere else again.” Mia stretched her arms above her head, her mouth open in a wide yawn. “Awww, why am I such a sleepyhead today?”

“You should sleep. It’s been a crazy twenty-four hours.” Homer looked at the map on his phone. “Besides, we’ve got lots of time before we reach anywhere that might have a hotel.”

“You sure?”

“Yeah. I like taking the smaller roads. It’ll make the trip longer, but it’s much more interesting than the highway.” What Homer didn’t say was that he was happy to draw out the time he had left with Mia for as long as he possibly could.

The old leather of the backseat crackled as Mia curled up. This time her face was turned away from Homer and she pressed her arms close to her chest instead of folding them beneath her head.

“Uh, Mia?”

“Yeah?” Mia said, tucking her knees up higher.

“I’m sorry. About your mom. It sucks.” Homer glanced in the rearview mirror. Saw Mia’s shoulders rise and fall, and then looked back at the road. Maybe she’s already asleep.

When she did speak, Homer could only hear some of what she said.

“Others have . . . worse. I was . . . because . . .”

Homer didn’t say anything else after that. And when Einstein woke up, he let him pick where they’d stay that night.

THE VISION OF A FAILED UTOPIA

“HOMES, IF I HOLD IT much longer, I’ll increase my chances of developing cystitis, which also puts me at risk for permanent damage to the kidneys and other internal organs.”

“Cist— What?” Homer looked down at the directions he’d printed at the Hideaway Motel’s business center that morning. He’d been in a rush and yanked the paper out of the printer before the

ink had had a chance to set, and so he was left with smudged directions to the one college he’d promised D.B. he’d visit.

“Cystitis. It’s the medical term for bladder inflammation.”

“Steiner, if you see a place, we’ll stop. But given that we’ve passed nothing but horses and farmhouses since we got off the highway, you’ll probably have to hold it until we get to Pillar College. Or you can water a tree.”

Homer glanced in the rearview mirror. Einstein’s cheeks were puffed out and he was squirming from side to side.

“You look like a blowfish right now,” he said, turning his eyes back to the two-lane country road. “At risk for cystitis? How do you come up with this stuff?”

“Really?” Einstein went from blowfish to puzzled, his head tilted in a way that suggested he didn’t know whether Homer was kidding or not.

“Yes, really.”

“I’m a genius.”

Einstein, Homer noticed, said “I’m a genius” the way another person might say “I’m six feet tall” or “I’m an enthusiastic fisherman.”

“What do you guys think about ‘Oscar’?” Mia had found a pair of sunglasses with plastic pineapples on the sides under the bed in her motel room that morning and hadn’t taken them off since. Homer couldn’t look at her without smiling. “Or ‘Penelope’? I could use ‘Penny’ for short. ‘Lucky Penny,’ that’s a cute nickname, don’t you think?”

“Name for what?” Einstein hollered from the backseat.

“For Tadpole, silly,” Mia said, shaking a paperback book in the space between the front seats. “I need a real name. Look what I found at the gas station while you guys were getting doughnuts.”

“One Thousand and One Names for Your Baby,” Einstein read. “If there’re one thousand and one names in there, I think you can find something better than ‘Oscar.’”

“Steiner, S.F.,” Homer said without much conviction. He was too busy trying to keep the Banana on the road while figuring out if he should be looking for Silver Pond Road or Slither Pond Road to put much energy into calling his little brother on his rudeness.

“No way that’s an S.F. Mia asked for my opinion, right?”

Homer saw Mia nod and wiggle back and forth as she turned the pages of her book. “Yup. Yup. I asked. Can’t get mad at the answer. What about ‘Ernest’? Or ‘Anastasia’?” She pushed the pineapple sunglasses back up her nose and tucked her candy-apple-red hair behind her ears.

That simple gesture, how Mia brushed her hair off her face, was so effortlessly hot that Homer had to force himself to look away.

“Now that I think about it,” she continued, “I should probably go, too. Bladder infection? No, thank you.”

“Really? Again?” Homer asked.

“Preggo ladies have to pee all the time,” Mia said as she reached down and shuffled the magazines at her feet until she found a particularly thick one. She set it on her lap. “According to Dr. Traynor—” Mia cleared her throat and, in an exaggerated accent somewhere between British and Australian, read, “During your pregnancy the amount of blood in your body increases by almost fifty percent— Wait, that wasn’t the part I wanted.” She began flipping through the pages. “I’ll find the part about needing to go all the time. Just give me a sec.”

“They have a magazine just for pregnant ladies?” Einstein asked, peering through the crack between Mia’s seat and the door.

“Nope.” Mia looked up. “It’s a parenting magazine. Homer got it for me when I found out I’d be having a Tadpole.”

“He did?” Einstein replied. “Isn’t that something the baby’s dad should—”

“Look, I can’t read the printout and my cell doesn’t get reception.” Homer said, dropping his phone in one of the Banana’s giant cup holders. “There’s a farm stand ahead. You guys can pee. I can get directions. Win. Win. Win.”

Mia clapped her hands together. “I hope they have pickled beets.”

“Pickled beets?” Homer asked.

Out of the corner of his eye, he saw Mia shrug. “Babies crave strange things, Homer. What can I tell you?”

“Guess I learned something today,” Homer said, taking a left turn at the sign for Doxy Community Farm Stand into a dirt parking lot.

“Oh, that’s nothing. Did you know that babies don’t have kneecaps and they can’t swallow and breathe at the same time for months and months? Plus . . .” Mia, still wearing her ridiculous sunglasses, continued talking as she slid out of the Banana and walked toward a red, shacklike structure with a hand-painted sign proudly declaring “Open All Year!!!” above the door. She was already inside by the time Homer and Einstein caught up.

“Huh,” Einstein said, scanning the dusky space. “I’ve never been to a farm stand, but aren’t they supposed to have . . . stuff? Farm stuff?”

The store was nearly empty save for a few jars of jam on a counter above an old-fashioned metal cash register and a handful of sad-looking potatoes in a bin close to the door.

“Maybe they’re closed,” Homer replied, swatting at the strings of cobweb he’d walked right into off his face. “You might need to water a tree after all, Steiner.”

“Nuh-uh.” Einstein shook his head and hopped from one foot to the other. “I’m still itchy from the bites I got yesterday—in places you can’t scratch in public.”

“Hello?” Mia called, pushing her sunglasses on top of her head as she stepped away from the lonely potatoes and farther into the shack.

“Hello! Are you here for the tour?” A voice, high-pitched with enthusiasm, bounced around the empty space. “Brother Bob is going to be so excited.” The tall man who strode into the shack through a door in the back right corner was dressed in denim overalls dotted with multiple patches, each a different color and pattern. His stained shirt had uneven sleeves, and his floppy straw hat was at least two sizes too big. “Bob, get out here! You have some folks here for the tour.”

“What tour?” Homer asked, but if the oddly dressed man heard him, he gave no indication.

“Okay.” The man clapped his bony hands together, then ran his long fingers through his stringy beard as if he were thinking deeply. “What can I tell you about our community? Let’s see, we’re a farming collective, in the spirit of Jeremiah Johacksenburg’s grand vision. We like to call him J.J. around here.” The man guffawed and slapped a hand against his leg.

Homer shuffled closer to Mia while the man was still doubled over. Just grab a corner of her jacket and Einstein’s shoulder and pull them both toward the door.

“Excuse me,” Mia said, raising her hand.

“No need for schoolhouse formalities around here, young lady.” The man swung his arms like a conductor leading an orchestra into a crescendo. “As J.J. once said, ‘We’re all students and the world is a corrupted classroom from which we learn nothing but how to bring about our own undoing.’”

Mia lowered her arm. “Mr. I’m-not-sure-what-your-name-is—who’s Jeremiah Whats-it?”

“You can call me Jenkins. Brother Jenkins.” The man leaned against an empty display that, according to the handwritten sign above it, once held “Organic Farm-Fresh Local, Free-Range, Gluten-Free Cabbage.” “I suppose I should start at the beginning. You’ll have to forgive me. It’s been a while since we’ve had prospective community members come for a tour. I’m a little rusty. Phew.” Jenkins whistled. “Okay, back to the start. Brother Jeremiah was a nineteenth-century visionary. He had the foresight to see that technology would one day destroy society, and in order—”

“He thought technology in the eighteen hundreds was bad?” Einstein interrupted. His squirming in the Banana was nothing compared to the dance he was doing now.

A cloud of confusion passed over Jenkins’s face. He was clearly not used to having his pitch interrupted, but after a moment his salesman smile returned. “Brother Jeremiah had the genius to understand that the air conditioners, the airplane, plastic, were all going to—”

“But—” Einstein interrupted again.

This time, he stopped shifting from one foot to the other but kept his hands pressed against the front of his pants. “Willis Carrier didn’t invent the air conditioner until 1902. The Wright brothers didn’t get a plane legitimately off the ground until 1903, and synthetic plastic wasn’t created until Leo Baekeland made Bakelite in 1907.”

Now Jenkins looked outright stunned and, Homer thought, a little panicky. “Well,” he eventually spurted, “think of those examples as metaphors. So as I was saying, Brother Jeremiah saw the destructive path the world was taking and took it upon himself to lead a chosen few to salvation. He established the first of many Johacksenburgian communities in the Adirondacks in 1842. His followers achieved harmony with nature. Avoided the temptations of the world. And they all lived happily ever after.”

“The end.” A guy in an outfit just like Jenkins’s minus the hat sauntered into the shack. “Did you tell them the next part of your inspirational spiel? About how we both gave up lucrative careers and rent-controlled apartments in Wallisburg to live off the land and be one with nature?” Each time the second guy made air quotes with his fingers, Jenkins flinched.

“Did Brother Jenkins happen to mention that there’re only two members of our utopian community?” The ranting guy threw his arms in the air and turned toward Homer, Mia, and Einstein. “Did I interrupt him telling you three all about how neither one of us can farm for shit and our own parents won’t join New Eden?”

“Brother Bob,” Jenkins said, his teeth clenched in a pained smile. “Language. The Powers That Be would not approve.”

Bob grunted and rubbed his chest. “I would give an arm for a pair of blue jeans. Hell”—he started scratching the back of his neck—“I’d give my nuts for clothing that didn’t itch like I was wearing a damn sheep.”

For a long, awkward moment, the only noise was the furious scraping of Bob’s fingernails against his skin.

Einstein was the first one to speak. “Do you guys have a bathroom?”

“We have an outhouse,” Jenkins replied brightly. “Built it ourselves from reclaimed wood.”

Einstein mulled this over. “Well, I guess that’s better than peeing on a tree.”

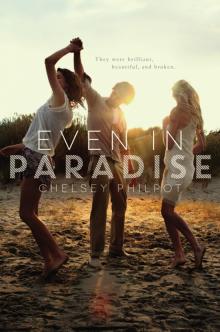

Even in Paradise

Even in Paradise Be Good Be Real Be Crazy

Be Good Be Real Be Crazy