- Home

- Chelsey Philpot

Be Good Be Real Be Crazy Page 4

Be Good Be Real Be Crazy Read online

Page 4

“Exorbitantly,” said Einstein.

Silence.

“Soooo.” Mia wiggled her toes in a wave—one way, then the other. “Christian looks happy. He must have gotten a good deal.”

“I hope he did,” said Homer.

“I concur,” said Einstein.

More silence.

“We could call it the Banana-mobile. You know? Because of the color—and the hood ornament.” Mia put her hands on her hips. “The thing is, I can’t decide if I hate it or love it.” She pressed a finger to her lips, considering her options. “I love it. The yellow grew on me.”

“That quickly?” Homer asked.

“Yup. Yup. Yup.” Mia took one step per “yup” as she hopped down from the porch. “Christian, are the cup holders big enough for Slurpees? Tadpole loves, loves, loves Slurpees.” She did a funny walk-jog-skip to the yellow car and then circled it, running one hand over the bright paint while Christian, from the inside, pointed and gave explanations that Homer couldn’t hear.

Homer, his raised left eyebrow a silent question, glanced at his brother.

Einstein shrugged in response. “Maybe it has an excellent fuel efficiency rating.”

“Okay.” Homer picked up his bag. “Let’s check it out and load up the rest of the stuff.” He and Einstein were halfway down the front walk when the screen door screeched open behind them.

“Few more safety items,” D.B. said, nodding at the two cardboard boxes he held balanced in his arms. “Extra bandages, more of Einstein’s Lac-Fab pills, road flares, that kind of thing.” He walked down the stairs two at a time and hurried toward the car’s trunk as if he were afraid Homer or Einstein would protest the additional boxes.

“You guys ready to go?” Christian slammed the driver’s-side door shut and clapped his hands together as he walked toward the house. He stopped and put an arm around Einstein’s shoulders. “Would you believe I only paid Ali one thousand dollars for this?”

“Not sure ‘only’ is the right word,” Einstein mumbled.

Mia had made her way back toward the house slowly, as though she was worried about interrupting. But when she reached Christian and flung her arms around his neck, all hesitancy vanished. “Thank you. It’s a great car. Thank you so much, for everything. This has been the best place I’ve ever lived.”

“Really?” D.B. said before he slammed the trunk hard enough to make the whole ugly, yellow car rattle. He still had to press down and jump on the lid before it clicked shut. “Jesus.” He wiped an arm across his forehead. “The trunk hinges need some oil or nonstick spray or something.” He circled around the side of the car to stand in front of Christian. “Mia, I have to say it one more time. If you get lonely up there or overwhelmed, Christian and I would love to have you.”

“I know,” Mia said, stepping out of Christian’s hug and vigorously shaking her head. “And I can’t thank you enough for everything you all have done for me. You’ve been crazy generous.” She shaded her eyes and stared so intently toward the place where the white sand of the beach met the turquoise water that Homer knew she was committing it to memory. “It’s so beautiful here, but I think Glory-Be-by-the-Sea is going to be great. Me and Dotts, we’re going to help each other. I’ll get a job. Maybe take some classes. We’ll get books and read to Tadpole.” Mia circled her arms around D.B.’s waist. “It will be super.”

D.B. caught Homer’s eye. He smiled knowingly and wiped his eyes on his left arm while he hugged Mia back with his right. As soon as she stepped away, D.B. pulled Homer and Einstein into a hug so tight, Homer felt like his nose was getting pushed in. “I’m going to miss you two so much.” His extra squeeze on “so” caused Homer’s elbow to press against Einstein’s right cheek.

“Ow. That hurts.” Einstein wiggled back and forth until his face was no longer smashed quite so much against Homer’s arm.

“Yes.” D.B. sighed loudly, but his usual levity was back. “Love does hurt, son. You don’t need to be a genius to know that.” D.B. shifted from side to side, leading Homer and Einstein in a slow circle.

“Oh, why are these here?” D.B. dropped his arms. Homer took a grateful breath as he turned around to see Mia standing by the open passenger-side door, a plastic-wrapped rectangle held above her head. “There’s like a gazillion of them in here.”

D.B. clapped his hands. “Disposable cameras. I thought they’d come in handy.”

Einstein must have given D.B. some kind of look, because he threw his arms up with exaggerated exasperation. “Come on. Disposable cameras are a thing again. They’re hip. Cool. Off the heezy. The bomb diggity.”

“Please stop,” Einstein interrupted. “I’m socially inept, and you trying to be cool makes me feel awkward.”

D.B. rolled his eyes. “Now that I feel my age, you kids need to take off before I have an old-man meltdown. Homer, you’ll call every night?”

Homer nodded.

“What are you waiting for, then?” Christian put an arm around D.B.’s shoulders and tossed a single key on a ring with a pineapple charm to Homer. “Get on the road. Go crazy. Have fun. Be happy.”

“Be safe,” D.B. said, his eyebrows pinched as if he were trying to remember something else he meant to say. “And be kind to people—even if they’re not kind to you.”

Homer pressed the sharp side of the key against his thumb. “Okay,” he said, throwing his bag into the back of the bright-yellow car and then sliding into the driver’s seat. “We’ll see you soon.” He waited until Mia and Einstein closed their doors and clicked their seat belts before he shifted the most hideous vehicle in the world into drive.

NOT AS IT WAS PLANNED, BUT AS IT MUST BE

THE FIRST DAY, THEY DIDN’T even make it out of Florida. The first night, they stayed at La Mancha Magnífico Motel. It was not magnificent—quite the opposite actually.

Homer and Einstein’s room smelled like the inside of an abandoned gym bag. Neither one of them slept under the suspiciously stained comforter on his bed, and Einstein put grocery bags over his feet before stepping into the narrow shower. Mia’s room reeked of cheap air freshener and cooked eggs, but she said Tadpole must like the smell because he or she was kicking like a ninja all night.

The second day started slowly. The three of them loaded luggage into the car like the bags had been stuffed with bowling balls during the night. Mia, who swore that she’d never liked coffee anyway, took a few sips from Homer’s third cup at La Mancha Magnífico Motel’s sad excuse for a free continental breakfast.

When they got back on the highway, Homer’s view from the passenger-side window was a slide show set on replay: subdivision, subdivision, splash of green, superstore, eighteen-wheeler, tollbooth, and repeat. The car didn’t have a CD player, never mind a place to hook up a phone, and the leather seats emitted an odor not unlike fruit left too long in the sun. The fact that the windows had to be rolled down with plastic handles didn’t help with the stale-air situation.

Homer spent much of the morning lost in his own head, hypnotized by the unexciting view and his worrying, until Mia broke into his reverie.

“Homer?”

“Sorry. What?”

“Homer.” Mia stretched out his name to twice its length. Hommmerrrr. “What’d I tell you about saying ‘sorry’ so much?”

“It’s his favorite word,” Einstein said over the pings and booms of whatever game he was playing on his handheld.

“No it’s not.” Homer turned to look at his brother. They were only a few hours into the second day of the trip, but somehow Einstein had already made the backseat look like Los Plátanos Pier the morning after a festival. Food wrappers and soda cans were piled on the passenger-side floor, various science magazines were splayed across the seats, and a small mountain of clothes dominated the space behind Mia. “Jesus, Steiner. Make yourself at home. Why do you have boxers on the floor?”

“I don’t know about you”—Einstein glanced up from his game—“but I like to be prepared. Great. There goes m

y last life.” He dropped his player on the seat. “The world’s going to end in seven days and I’ll never have made it past level six.”

“Don’t feel bad.” Mia looked over her shoulder. “One of my—”

Beeeeeeeeeeeeeep. The driver of a delivery van kept his horn pressed until Mia jerked the car back into the right lane.

“Oops,” Mia shouted at her closed window like she thought the delivery guy could hear her. “Lo siento. Anyway, when I lived with the Gardiners—they’re the family with two bio kids and a rabbit named Shiloh—two foster boys, twins actually, came in the last month I was there and one of them, Tucker, wet his pants sometimes even though he was eight. Mrs. Gardiner told me he’d grow out of it and to stop babying him.” Mia frowned. “She was one of the bad eggs. Phew. I made sure Tucker had a clean pair of underwear in his backpack. I told him it was a secret.” Mia smiled. “He liked that. I think it made him feel special. I’d put the new pair in a plastic lunch container just in case anyone peeked in. Maybe you should do that, Steiner.”

If anyone else in the world had told his genius little brother to carry a spare pair of boxers in Tupperware, Homer would have been waiting for the punch line, but Mia’s expression was earnest, her voice kind. She’d probably give a dictator her last tissue if he had a cold.

“Uh, okay. Thank you for the suggestion, Mia,” Einstein said, shifting forward so his knees touched the back of Homer’s seat. “But I don’t wet my pants.”

“It’s okay.” Mia reached back to pat Einstein’s leg, but he was too far on the passenger side for her to touch. “Tucker was embarrassed, too.”

“No, I swear, the only reason I have underwear out is because if the Giant Atom Accelerator goes off early, I want to die wearing clean boxers.” Einstein’s protest was punctuated by squeaks from the backseat springs

Homer rolled his eyes. “You’re telling us that in the highly unlikely event that an experiment in a can buried miles beneath the ground causes a ginormous black hole, you believe you’re going to have time to change your underwear before the aforementioned black hole swallows the Earth?”

“First, it’s the Giant Atom Accelerator, not a can,” Einstein said, flopping back against the seat and crossing his arms. “Second, it would take me days to explain the effect a black hole could have on the properties of time in this dimension.”

“Oh, we have time,” Mia said. Homer turned around just quickly enough to catch her making her thinking-guppy face as she tried to see the road hidden by the driver’s-side blind spot. “In fact-ta-roo, I’m going to get off the highway, because if I see one more minivan doing eighty, I will go bananas. Sorry, Banana.” Mia patted the steering wheel. “We can take some small roads and Einstein can explain science stuff.” She pointed at her stomach. “This way, Tadpole will grow up to be super, super smart. And then we can stop for lunch and then we can find a camping ground because we have the nifty tents.”

“No way. Those tents smell like melted crayons.” Einstein snorted. “I don’t think the dads have ever actually used them.”

“Oh.” Mia’s expression changed so quickly, she looked almost like an entirely different person. Or maybe it wasn’t the change so much as the shock of seeing her look unhappy. Most people’s most-of-the-time faces were neutral: their lips neither curved up nor curved down, their eyes neither shining nor dull. But Mia was different. Her most-of-the-time face was dimples showing, lips slightly parted, and eyes open like she was afraid of missing something.

“S.F., Steiner,” Homer said.

“How was that a social fail?” Einstein demanded, but then he must have caught Mia’s reflection in a window. “Oh, we can go camping. Sounds like”—Einstein’s eyes met Homer’s in the side-view mirror—“fun.”

Homer nodded. “Good job,” he mouthed.

“I’ve never been camping,” Mia said as she clicked on the blinker and pulled onto the exit ramp. Her voice was already a little brighter. “And I really do want Tadpole to be smarter.”

“Smarter?” Einstein said. “Than me?” His tone was marked by disbelief, but Homer figured he’d just called him out on a social fail, so he’d let this one slide.

“Smart. I meant smart. I can’t believe this song is on again. I love, love, love, love it.” Mia turned the volume knob 180 degrees to the right. She started humming, then glanced at Homer. “New rule. If you’re driving, you get to control the radio.”

“That hardly seems—” But Homer’s protest was drowned out by pop music as Mia turned the volume even louder and belted out her own off-key version of an already terrible song.

“Oh. Oh. Maybe tonight is the last song of this life.

Oh, tonight’s da, da, da, da song of our lives.”

Three hours later, while Homer and Mia switched seats, Einstein asked the two women smoking in lawn chairs by the Whistle and Pop Convenience Store entrance about local campgrounds. The smaller woman looked at him suspiciously, but the other one told him the only one open this time of year was two towns over, in a “hoot” of a place called Pythia Springs.

Not long after they got back on the road, the radio began to cut in and out, the signal turning to pure static when they reached the first sign: a massive billboard with two rows of gold-tinted spotlights, one above and one below. The whole thing shone like it had been dipped in plastic, and the color and font of the message made it sound less like an invitation and more like a demand: “Visit Pythia Springs, Home of the World-Famous American Oracle.”

“I haven’t seen that movie,” Mia said in her singsong voice as she continued to focus on the intricate pattern of leaves, vines, and flowers she was doodling on her left forearm. She’d been drawing for the better part of an hour, starting at her wrist and working her way up to her elbow.

Einstein shook his head vigorously. “It’s not a movie.” He paused, glancing at Mia’s homemade tattoo. “All that copper phthalocyanine can’t be good for your skin.”

“Aren’t you sweet, worrying about me.” Mia twisted and reached between her headrest and seat to pat the top of Einstein’s hair.

Homer hadn’t been jealous of Einstein in years, but something about Mia’s easy affection for his brother lit a match in his chest. It burned for a moment, then went out, leaving a different feeling behind: shame. He’s your brother, you idiot. He stayed up past eleven to help you with your seventh-grade science fair project. Homer whispered the thoughts. Even in his own mind, he didn’t want them any louder.

“American Oracle,” Mia said as she leaned toward the windshield, squinting at a sandwich board sign set up just before a bend in the road. “Three miles.”

“Okay,” said Homer, gripping the steering wheel much tighter than he needed to. “This is getting a little weird. You sure we have to camp here?”

“The nice lady said it was the only place open in December.” Mia held her arm up, admiring her artwork. “What do you guys think of Pythia as a name for a girl, or Oracle for a boy?”

“Uh, I—”

“Brake!” Einstein yelled.

Homer slammed his foot on the brake pedal without thinking, bringing the Banana to a stop less than a foot from the bumper of the SUV in front of them. The air instantly smelled like hot rubber, and the Banana’s engine cranked and sputtered before shutting down completely. Homer felt like his heart could break the bones of his rib cage, it was pounding so hard. “Everyone okay?”

“Phew, Homer.” Mia pushed herself off the dashboard and sank back into her seat. “Good thing I had names ready, because if you’d slammed those brakes even a smidgen harder, Tadpole might have shot right out of me.”

Homer couldn’t tell whether Mia was being serious or joking. Probably should assume “not joking.” “Sorry. I wasn’t paying attention.”

“What’s with all the cars?” Einstein asked, pointing between the front seats.

Homer looked forward. A line of cars, vans, and trucks stretched in front of the Banana. The lights from countless brakes tapping on

and off reminded Homer of blinking Christmas lights. Before he could think of a response to Einstein’s question, the cars that had rolled in behind him started honking. It took three tries, and some mumbled swears under Homer’s breath, but the Banana’s engine finally caught and they rolled forward, just one more car in a caravan.

The dark woods that lined the road eventually gave way to run-down, abandoned buildings, each uniquely neglected and sad in its own way. The first one, a former gas station, resembled an unevenly baked cake. The hoses from the two pumps stretched across the crumbling asphalt like emaciated snakes, and the triangles of glass that framed the smashed windows and rusted door of Pythia’s Finest Convenience Store were pointed teeth in a gaping mouth, revealing the empty shelves, cracked floor, and debris within.

A Victorian house two blocks after the gas station had railings leading up to the front door, but no steps. The rusted letters on a rotting sign propped against a tree stump read “Pythia Springs Inn,” but the way that kudzu vines reached out of the windows like a giant squid’s arms made it clear that it’d been a long time since the inn had had any guests.

The redbrick library was missing one of its four walls, the open side displaying piles of moldering books, chairs with missing legs, and toppled shelves. The building across the street from this diorama must once have been a church, but now it had a tree poking through a hole in the roof. Most of the other buildings were impossible to categorize because weather, neglect, and time had eroded their purposes.

“This place is so . . . lost,” Mia whispered. She shook her head. “That’s stupid. It doesn’t make any sense.”

“No,” Homer replied. “‘Lost’ is as good a word as any.”

At the same time, Homer thought “lost” wasn’t quite enough. It was a forgotten place. A place saturated with old sadness.

The disarray made the next sign seem even more garish than the first billboard they’d passed. “Welcome to Pythia Springs, South Carolina. Home of the American Oracle. Park Here.” A giant arrow at the bottom pointed to a parking lot that was easily three times the size of the largest one Homer had ever seen. It was a field of black—the asphalt so new it glistened like it was still cooling to solid. Men and women wearing fluorescent-orange vests waved cars into rows and directed the vehicles’ occupants to the sidewalk, to join the river of people all flowing in the same direction. Homer ignored the turn-here gesture of the fluorescent-vest man at the entrance and kept driving straight. He didn’t know where he was going, but he knew it wasn’t there.

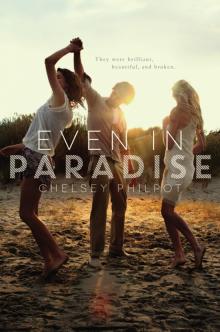

Even in Paradise

Even in Paradise Be Good Be Real Be Crazy

Be Good Be Real Be Crazy