- Home

- Chelsey Philpot

Be Good Be Real Be Crazy Page 18

Be Good Be Real Be Crazy Read online

Page 18

“Oh, I’m not supposed to be here,” Mia said apologetically. “I drove up to say ‘sorry’ to Homer.” She pointed across the table at him. “Not for the conference. But,” she added, “your barn is very nice. I’m glad I got to see it. Very old meets new.”

Dr. Az clapped his hands. “This may be the easiest group I’ll ever have.” He shifted, indicating that Homer’s turn was next. “Though there’s always room for a grand inquiry about the cosmos.”

“I think . . .” Homer looked up from the floor, letting his eyes meet Dr. Az’s. “I think that I’m still coming up with questions.”

“But you’ll get there?” Dr. Az said.

Homer half smiled. “Yeah. I think I will.”

“Good.” Dr. Az hopped off the lab table. “Now you young people will have to excuse me. I have a keynote speech to finalize and I believe you’re already late for the party.” Dr. Az squinted at his watch. “Yes, six twenty-two. It’s begun.”

“Party?” Sid asked as he shook Dr. Az’s hand.

“It’d be rude to meet the end of the world without one.” Dr Az replied. He clapped his hands twice and a light turned on over the now-open door. “Even ruder to not celebrate humanity’s survival if that’s the direction the night takes.”

Einstein followed Sid, then Mia followed, and finally Homer shook Dr. Az’s hand and moved toward the door.

“Homer?”

Dr. Az’s voice made Homer pause a few feet from the exit and the new night. “Yes, sir?”

“We’re all just bunches of atoms, the same ones that were here at the beginning.”

Homer swallowed. “Right. I know. The Big Bang.”

“The atoms that make up you, the ones that make up me, they just as easily could have formed the rings of Jupiter, a comet, or one of the innumerable stars.”

“Oh, that’s neat.” Homer wasn’t sure how he was supposed to respond, and the awkward way he had turned was starting to make him wobble.

“A great poet led me to this understanding. Not Galileo, Mitchell, or even your brother’s namesake.” Dr. Az pressed two fingers to his temple as if he needed the pressure to remember. “The stars are watching, and they envy us,” Dr. Az said, lowering his hand. “Our atoms got lucky, Homer, yours and mine. They got to become human. To waste a moment of that cosmic blessing would be an insult to the not as fortunate stars.”

“I think I understand.”

Dr. Az nodded. “Good.”

THE PARABLE OF THE FUTURE MAD PHYSICIST

IT TOOK YEARS FOR THE Future Mad Physicist to get used to the wet cold of North America. It was so very different from the cold of the country where he was born, which was a dry desert cold that even at its January worst stayed above freezing. Perhaps the contrast wouldn’t have seemed so drastic if the years that the Future Mad Physicist spent in the refugee camps hadn’t been so hot.

The day of his final resettlement interview had been particularly brutal. The Future Mad Physicist had nearly fainted as he sat on a metal chair trying not to choke on the plastic-baked air in one of the imposing white tents just outside the camps. It could have been the heat or it could have been the fear: he was terrified of answering the uniformed man’s questions incorrectly. If he did well, he would join his father’s brother in America. If he failed, he would have to stay. A life in the camps. A life spent in neither Here nor There, but somewhere In Between.

The Future Mad Physicist had always been a diligent student. He studied the interview questions for months, preparing two answers (one spoken, one silent) for each.

Do you believe you were persecuted for your religious beliefs in your country of origin?

Spoken: Yes.

Silent: Persecuted? It seems such a trivial word when death is the price so many have paid for having a faith that those in power don’t share.

Should you return to your country of origin, do you think your life would be in danger?

Spoken: Undoubtedly.

Silent: The men who came for my father were neighbors—men he trusted. He went with them, thinking he was walking in the direction of negotiation and peace. I hope the moment that he realized he was moving toward his grave was only seconds before they killed him. These men know my face. Returning home would be a death sentence.

Do you find it difficult to procure necessities, such as food, water, and clothing, in the refugee camps?

Spoken: Life in the camps isn’t easy, sir. But I am grateful to be here. Many have not been as fortunate.

Silent: I wish I were a poet. Then I could spin words in such a way that you would understand what it’s like to run from one hell into another, more terrible and soul-crushing than the one before. In the camps, I have come to understand that hunger can hurt in your bones and that not being able to do anything, not even cry, to ease another’s suffering is the cruelest torture on Earth.

I am only a young man, but in my twenty years of life, I have witnessed such pain and loss that my father’s faith has been taken from me. I am no longer afraid of death. But I have much to do before it arrives.

If granted asylum in the United States, what will you do to become a contributing member of society?

Spoken: I plan on enrolling in an American university as soon as possible after my arrival. I will become a scientist.

Silent: I’ll make it my life’s work to find explanations where most think there are none. I’ll try to do good and avoid doing harm. I’ll become a man my father would have been proud to call his son.

The Future Mad Physicist was older than most of the other first-years at the American university where Amu, his uncle, taught literature and poetry. He seldom had a class outside the science building and never took one of Amu’s courses, but on the day his uncle was teaching Rumi, the Future Mad Physicist snuck into the literature auditorium to listen to his uncle read.

“A moment of happiness . . .”

The Future Mad Physicist closed his eyes and let the words wrap around him.

“We feel the flowing of life here, you and I. . . .”

For the span of the class, he let himself imagine that the voice reading his father’s favorite poet was indeed his father and that the smells of the classroom (air freshener and new paper) were replaced by those of the city where he once lived (rose water and fine dust).

“The stars will be watching us,

. . .

In one form upon this Earth,

and in another form in a timeless sweet land.”

The Future Mad Physicist was so deep in his memories that he didn’t realize that the class was over until he felt Amu’s hand on his shoulder.

“Rahman Joon,” Amu said. “Are you well?”

“Yes,” he answered, even though he wasn’t.

He would be.

Someday.

The future, he reasoned, was as good a thing as any to believe in.

THE WATCHING OF THE END OF THE WORLD

“WHAT DO WE DO NOW?” Sid asked once the huge door had shut behind them. “It’s cold out.”

“We go to the party and wait for the end of the world,” Homer said softly as he started walking toward the farmhouse, where every window was a glowing rectangle and a jazzy song in a language he couldn’t place pushed out from under the front door, skittering across the porch like each note was a crystal tossed by an invisible hand.

Einstein lightly punched Homer’s arm as he jogged up to his left, Sid beside him. Mia stepped silently to Homer’s right side. As a straight line of four, they crunched over the frozen grass, moving from the dark to the light.

The farmhouse’s entry room narrowed to a hallway before opening into a ballroom-like space packed with conference goers. In the far corner, a few couples waltzed to the strange music while circles of men in wrinkled suits and women in dresses that sparkled spoke in shoulder-to-shoulder groups throughout the room. Sid and Einstein made a beeline for the food tables just a few steps into the party, leaving Homer and Mia alone.

Homer p

ointed to the set of bleachers just to the right of the dance floor. “Want to sit down?”

Mia shrugged. “Okay.”

Homer took longer than he needed to figure out how to fit his legs behind the second row of seats. When he finally stopped squirming, Mia didn’t say anything. For half a heartbeat, he wasn’t sure she would.

“Trisha said you came back, to look for me.” Mia kept her eyes on her hands as she spoke.

Homer swallowed. “Yeah. I thought maybe you’d go there.” He couldn’t tell if he was turning red or if the top row of bleachers was the stuffiest place in the room.

“She likes you.” Mia smiled sadly. “She said you were one of the good ones.”

“She’s really nice. I think her life hasn’t been easy—either,” Homer added lamely.

Mia glanced sideways at him. “Maybe that’s why she said I could have the apartment.”

“What?” The two women in the second row glared over their shoulders at Homer.

“Shhhh,” the taller of the two whispered. “Dr. Az is going to speak.”

Homer glanced at the front of the room. The groups of talkers had been pushed back to create a half circle of open space. The only thing there so far was a lonely microphone on a stand. “Did you say yes?”

“I—”

Sid and Einstein clambered up the bleachers, each balancing an overloaded plate, and sat down in the row in front of Homer and Mia before Mia could finish answering.

“They have brownies,” Sid said, smiling so widely it seemed like he was using his chocolate-covered teeth as proof.

“Quiet. Az is speaking.” Einstein nudged Sid and pointed to the microphone, where Dr. Az now stood.

Thank you. This might be our largest conference yet.

Dr. Az’s voice was deep and smooth. If he had been nervous about speaking, it didn’t show.

Thank you to my colleagues at I-9 who graciously donated valuable research time to conduct workshops and deliver papers. What an opportunity, to hear from the world’s greatest thinkers addressing the world’s greatest problems. Thank you to participants who have come from all over to be here tonight. I’d like, in particular, to recognize our youngest participants, who drove a great distance in search of knowledge.

Sid punched Einstein’s shoulder “That’s us!”

“Ow.”

Now, we only have one hour and fifteen minutes before the end of the world. So I’d better get started.

Some people chuckled. Many, including the women who had given Homer nasty looks, did not.

Dr. Az waited for the crowd to settle before he pressed on. When he did, Homer whispered to Mia, “Are you going to?”

She nodded. “I’ll take care of Baby Goober to pay rent. Tadpole will have someone to play with. There’s already furniture and stuff. . . .” Mia’s voice trailed off.

The world will cease to exist one day. That is certain. But how and when—that’s the mystery. The universe began with a bang—but it could end with a whisper.

Homer heard Dr. Az, but not really. It was like his words drifted into Homer’s ears but couldn’t reach his spinning brain.

“Do you—” Mia stopped speaking when the tall woman gave her a look that could have melted ice.

Homer gestured toward the door that someone had propped open near the end of the bleachers. Mia made an “okay” sign with her hand and carefully slid in that direction. Homer touched Einstein’s shoulder to let him know where they’d be.

His little brother’s glasses were smudged, he had crumbs on his shirt, and when Einstein mouthed “Good luck,” Homer wished he had space to hug him. He settled for pretending to mess with his hair and silently replying, “Thank you.” Then he followed Mia into the night.

Mankind is so arrogant and foolish as to believe that the story of the universe could be any different from the stories we tell. The stories that all have a beginning. A middle. An end.

Dr. Az’s voice followed them to a picnic table at the base of a small snow-covered hill. Homer watched Mia pick a spot before he hopped up and sat beside her on the top of the table.

Homer waited for a round of applause to die down before he spoke. “Why? Why Glory-Be if Dotts isn’t there?”

Mia looked at her hands. “It’s more a feeling than a reason—something telling me that it’s where I need to be, for now at least. I know that sounds silly.” She picked at imaginary strings on her coat. “I can take classes at the community college. Trisha said that I could borrow her car and that she’d teach me how to cut hair. I think I’d like it, cutting hair, making people happy.”

Homer tilted his head back and fixed his eyes on the stars. If you believe in gravity, you already believe in something higher than yourself. Out loud he said, “I think you are so much smarter than you give yourself credit for.”

Even people of science must have faith.

“You mean that?” Mia crunched the heel of her sneaker on a patch of ice that clung to the picnic table’s bench.

“Of course I do.”

Mia smiled shyly as she gathered the broken ice into a pile with her foot. “Did you know Tadpole’s dad wanted to marry me? He proposed over the phone when I told him I was pregnant. Said he still didn’t know why I left, yada yada yada.” On the final “yada,” Mia kicked the pile of broken ice she’d created into the air.

The bits that made it far enough to catch the light from the open door glistened like pieces of a broken chandelier before disappearing into the snow.

So we keep tying our shoelaces.

“Why’d you say no?” Homer tempered the jealousy that sparked in his chest.

And turning car keys.

“Because I need to prove something to myself. I don’t know what, but it’s important.”

Doing dishes, mowing lawns, and brushing our teeth.

“You’ll find out what.”

We keep praying and asking and breathing and loving—

“You will, too.”

Because it’s an imperfect miracle of atoms and chaos that we are here at all.

“Plus, I was already in love with you.” Mia’s voice shook as she spoke. “And before you say anything, I want you to know that I know I’ve got things to figure out and that stealing the Banana was so, so wrong.”

“If you had let that car roll off the side of a mountain, you would have been doing the dads a favor.” Homer’s heart felt like it was pressing against his lungs. Mia said she loved me? She. Loves. Me. Back.

“It really is hideous.” Mia sniffled. “Isn’t it?”

“And it smells. We could leave the keys in the ignition and put a sign that says ‘Steal Me!’ on the windshield and no one would touch it.”

Mia’s laugh cut through the cold air like lightning slicing through clouds. “You’re special, Homer. You don’t see it yet, but I hope you do soon.” Mia tilted her head to the side. “Can I kiss you?”

Our species is so young and so ancient.

“Not because you feel bad for me?”

Mia shook her head. Tears, clear pebbles of salt water, had drifted down her cheeks.

“Then why?”

“Because I want to.”

We are so tough with our souls of brick and iron.

“Okay.”

We are so fragile with our hearts of paper and glass.

Mia’s lips were chilly and soft when she pressed them to Homer’s neck, but warm by the time she’d kissed her way to his mouth. In the pause between, when Mia’s lips hovered just above his, Homer gently wrapped his hand around the back of her neck, bringing her as close as he could, carving a pocket out of the night that began and ended with them. Her skin felt smooth even to his cold fingertips. He could count her heart beating through a vein in her neck. One. Two. Three.

Then they kissed and the universe came rushing in and the pocket they’d created exploded and Homer realized that that was okay and he let himself fall into the uncertainty because he understood now the unpredictability of it all.

/>

The kiss was wonderful and amazing, but also sad. Most good-byes are.

Maybe a thousand years from now we will no longer recognize ourselves as we are today.

When Mia pulled away, Homer watched the white clouds of her breath blend with his, drifting upward, until they disappeared and became part of the cloudless night.

And maybe in a thousand years we will still be trying to understand just how to be.

Mia wrapped her hand around the back of Homer’s neck and he kept his on hers. He needed to be touching her to be strong enough to say what he needed to say.

Maybe we will have the same questions and the same lack of answers.

“That was a good-bye, wasn’t it?” Homer said, touching his forehead to hers.

It doesn’t matter.

“Not a forever one,” Mia whispered. “It’s a let’s-see-what-happens good-bye. Besides”—she laughed even as tears slid from her eyes to her chin—“I need one last ride. To Glory-Be.”

Homer smiled and used the sleeve of his coat to wipe off her cheeks. “Well, you’ll get to see a very angry D.B. Tomorrow morning’s the first flight he could get. Einstein and I are supposed to meet him in Boston. At least now we can drive.”

We—

“Can I have the cameras?” Mia pressed her face into Homer’s neck. The warmth and realness of her made it hard for him to swallow.

Will—

“Sure. You’ll have to find a place that develops film.”

Still be—

“I’ll send you copies. But only of the good ones. There are probably a million bazillion photos of the floor mats and Einstein and Sid snoring in the backseat.”

Here.

“Promise.”

“It might take me a while.”

“I’ve heard that stuff that matters takes time.”

Mia leaned her head against Homer’s chest. For a moment, they watched white shards shower down from snow-heavy branches and fall through the dark sky to join the luminous covering on the ground.

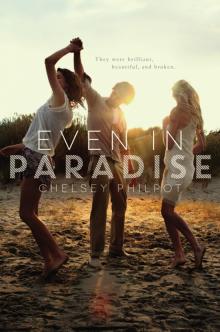

Even in Paradise

Even in Paradise Be Good Be Real Be Crazy

Be Good Be Real Be Crazy