- Home

- Chelsey Philpot

Be Good Be Real Be Crazy Page 13

Be Good Be Real Be Crazy Read online

Page 13

“What do you mean?”

“It wasn’t just that I didn’t believe in anything, it was that I didn’t believe I could believe. Does that make sense?”

“Actually, it does.” Mia rubbed her stomach. Her voice sounded saturated. Even though she whispered, the words were heavy. “It makes a lot of sense.” Mia paused. “Homer, would you do me a favor?”

“Let me guess, ice-cream run.”

“Close your eyes.”

“Uh, why?”

“Because I want to kiss you, and if you have your eyes open, I’m afraid I’m going to chicken out.”

Homer wiped his hands against his pants. Ducked his head. Looked at the river. Wished he could scrub his face against his sleeve or check his breath against his palm.

“Please.”

It was the way she said “please,” like the one word was both a demand and a question. So he did. Homer closed his eyes.

He expected her lips on his, but that wasn’t what happened. First, Homer felt her breath on his neck, right below his left ear. A warm whisper against his cold skin. Then he felt her lips pressed to the very same spot, making him shiver in the way that only goose bumps can. He felt his hip bump against the railing, but just barely. Her lips left a trail of fruity gloss as she gently kissed Homer’s jaw, left to right, and then finally put her mouth to his.

Kissing her was not like anything he could have imagined.

The first time they broke apart, Mia rested against Homer’s chest, her hair tickling his nose. The second time they kissed, Homer opened his eyes, just for a moment. The third time, they only stopped kissing because the police officer Renata had promised would be guarding the park yelled at them to get inside.

So they did. Holding hands and laughing as they danced over the path of broken glass and out of the night.

They fell asleep side by side on one of the twin mattresses Renata had distributed across her apartment floor. And even though he was terrified about bumping Tadpole and morning breath and a million other things, Homer fell asleep holding Mia’s hand.

That was all. That was everything.

THE CAR OF CELESTIAL STINK AND THE TOWN OF UNEXPECTED EVERYTHING

WHEN HOMER WOKE UP THE next morning, his first thought wasn’t to wonder where he was or how someone had painted a pattern of swirls and circles on Renata’s ceiling. His first thought was that today was the day they’d reach Glory-Be and he’d say good-bye to Mia. His second thought was an extension of the first. How has anyone ever, in the whole history of the universe, survived a broken heart?

As Poncho had promised, Martha was very hungover and a very good mechanic. She had already been tinkering under the Banana’s hood for hours when Homer and Einstein stumbled out of Renata’s building to hunt down coffee, bagels, and the vitamin C tablets Renata swore were the only way to counteract too much cheap rum.

By a little after eleven, Martha slammed down the hood. It was the strangest engine she’d ever worked on, she said, but it was fixed.

Poncho shook their hands and Renata gave them all hugs and accused them of making her puffy-eyed. And then Mia was behind the wheel, Homer in the passenger seat, and Einstein and Sid were in the back, comparing notes from the party and each trying to outdo the other with “cools” and “awesomes.”

Two hours into the long drive from one end of Massachusetts to the other, Homer couldn’t ignore the smell any longer. And even though the DJ for whatever station Mia had chosen promised that it was “a cold one out there,” Homer cranked down his window and tried to inhale as much fresh air as he could.

“Shut the window. It’s freezing,” Einstein yelled from the backseat. With his sweatshirt hood pulled up and his glasses askew, he looked like an angry owl.

“It’s kind of fun,” Sid said, leaning over Einstein. “Hey, do you think this is what it’s like to be inside a freezer with a fan?”

Homer took a final deep breath of air scented with frozen dirt and grass. He’d started to roll the window back up when the smell struck again. “Aww, Steiner, I know you’re lactose intolerant, but that’s just rude. Major S.F.”

“I didn’t fart.”

Homer pulled his shirt over his nose, so his voice was muffled. “Sure.”

“Maybe we ran over a skunk,” Einstein said before he ducked his nose into his sweatshirt. He looked even more like a grumpy bird.

“Homer, the car’s smelled terrible for days.” Mia swallowed like she was trying not to laugh. “How have you not noticed until now?” She turned her eyes back to the road as she passed a tractor trailer and a large SUV.

“See?” said Einstein, his voice muffled by his sweatshirt. “Even I know not to fart in a closed environment.”

“It has?” Homer took his nose out of his shirt.

“It smelled like a combination of rotten fruit and burned coffee when I got in here.” Sid stuck his face between the two front seats. “And it’s gotten worse every day since. Maybe you did run over a skunk and it’s stuck in the engine?” he added helpfully.

“It’s not skunk,” Mia said as she flipped through the radio stations. “It’s like its own powerful, disgusting combination.”

“Yeah.” Einstein kicked the back of Homer’s seat as he sat up. “It’s pineapple mixed with old leather and stale chips.”

“Whose fault are the stale chips?” Homer called over his shoulder.

“Don’t look at me,” Einstein replied indignantly. “I’m not the one who didn’t know chips were crumbly.”

“In my defense,” Sid said, raising his pointer finger, “I had never had chips before.”

“It’s more like a swamp that’s been sprinkled with powdered sugar and put under a heat lamp,” Mia said.

“Good one.” Einstein nodded.

“Dirty sneakers left in a locker room with a broken thermostat,” Homer said.

“This car smells like an outhouse,” Sid chimed.

“Lame,” Einstein responded. “How about . . .”

The game went on for the next thirty minutes or so, but Homer stopped noticing the smell—or, really, much of anything else—when Mia reached across the console and rested her hand on top of his. Her simple gesture, the feeling of her hand on his, was just enough to remind him where they were going and what he was losing.

The closer they got to Glory-Be-by-the-Sea, the quieter Mia became and the slower traffic went. When Homer said something about how weird it was that Route 16 was this backed up in December, she nodded, but that was it.

Mia drove and Homer reminded himself to breathe. When he tried to pull his thoughts together into what he wanted to say, his mind became a bunch of rocks scudding down a mountain and his heart felt more and more like a waterlogged stuffed toy. Outside the Banana, horns honked and music thumped through car radios, but inside, Einstein and Sid snuffled and snored in the back and the cracked leather of the passenger seat sighed as Homer shifted so he could rest his arm on top of the empty cupholders and hold Mia’s hand. Without looking over, without taking her eyes from the road, she turned her wrist so she could weave her fingers through his, and she pulled his hand to her cheek.

When she lowered her arm, she sighed but didn’t let go of his hand. Not even when they drove by a large, faded billboard that declared in bold black letters “Congratulations! You’ve Reached Glory-Be-by-the-Sea!” and Homer managed to not choke on the directions he didn’t want to give, for Mia to take the next left turn. Not even then did she let go.

If it hadn’t been for the crowd of people streaming over the sidewalks and streets like a massive school of fish, Glory-Be-by-the-Sea would have been the epitome of a resort town in winter. Any other day, Homer thought, this place might be pretty.

The beach dunes looked crystallized, like handfuls of sugar had been tossed on top of the sand. Thin patches of snow hid in shadowed corners and other protected places like hibernating animals. Most business windows were covered with plywood, the stores’ flagpoles naked, the signs on the doors al

l turned to show the “Closed” side.

Mia drove by three parking lots before she found one that had spaces left. She was reaching to hand money to the parking-lot attendant, an old guy in overalls and flannel, when Einstein poked his head between the front seats.

“Sir. What’s going on? Why are all these people here?” He sounded like he was still waking up.

The attendant shuffled Mia’s bill into the roll he had pulled from one of his many pockets. He tipped his cap up, licked a finger, and counted off three one-dollar bills and handed them to Mia. “New thing they’re testing at the Salvation Ballroom. Having a winter concert series. Trying to keep the money rolling in year-round.” He spoke each word deliberately, like he didn’t want to waste a single one on explanations.

“Who’s performing?” Sid tried to shove his face next to Einstein’s, but gave up when Einstein wouldn’t move over.

“Guy called Apollo Aces.” The old man shrugged. “Not my cuppa, but show’s been sold out for months. You kids fans?” He pulled his hat brim down before bending so his face was even with the window. “’Cause if you are, I might be able to get my hands on some tickets. There’s a courtesy charge, of course. Something along the lines of—”

“Yes!” This time Einstein let himself be pushed back so Sid could lean into the front. “How much for four tickets?”

“Two.” Homer cleared his throat. “You two should go. I’ll help Mia with her stuff . . . and stuff.” He would have smacked his forehead if he could’ve without calling more attention to his lameness.

“Awesome,” Sid said, falling into the backseat just long enough to dig money out of his backpack before he shoved himself between the front seats again. “Is two hundred dollars enough?” Sid reached over Mia and held two crisp bills out the driver’s-side window.

“You raised beneath a rock, kid?” the parking-lot attendant asked as he snatched the bills with one hand while the other grabbed two tickets from his coat pocket. “You can’t wave money around like that. Here.” He handed Sid the tickets and pointed vaguely to the lot behind him.

“Thank you,” Sid said as he slid into his seat. He and Einstein stared at the slips of paper like they couldn’t believe they were real while Mia rolled up her window. “This is the coolest.”

It took some circling around for Mia to find an empty space large enough to fit the Banana, but less than one minute to decide on the plan: Homer and Mia would walk to Dotts’s place. Einstein and Sid would follow the crowd to the Salvation Ballroom. They’d meet back at the car after the concert to say good-bye to Mia.

At the parking-lot entrance, Einstein and Sid turned right and were soon caught up in the flow of people. Homer and Mia turned left and walked against the current of excited concertgoers. Mia reached for Homer’s hand and he let himself be pulled behind her.

After a few minutes of following, Homer knew when Mia was going to turn left and when she was going to turn right almost at the same time she did. The farther they got away from downtown, the narrower the streets became, and the closer the tiny houses with neat yards, picket fences, and tidy white trim grew together.

At the turn for Seahorse Street, Homer promised himself, I’ll say something by the house with the red mailbox. Definitely, by the final house. But as they shuffled onto Blueberry Lane, Homer felt like he would choke on everything he wanted to say but couldn’t.

Okay. If a car passes by before the end, I have to say something. I need to say something. A white van with rusted doors and “Henry’s Finest Seafood” across the side rolled by, so Homer cleared his throat. “Mia?”

He must not have spoken loudly enough, because Mia turned onto Ocean Avenue and stopped at the second house on the right side of the street. Only after she started pushing the gate—which stuck against the uneven path like it too was protesting her decision—did Mia look up.

“Ready?”

Homer wasn’t, but he nodded anyway, dropped Mia’s hand, and then walked up and rang the bell, reciting Let nobody be home. Let nobody be home. in his head like an incantation.

The door opened immediately. “Hello. You here about the apartment?” The woman who stood behind the screen door was tall and pretty, though obviously exhausted. She had purple smudges under her eyes and she leaned against the doorknob like she needed help to stay upright. The only parts of her of that didn’t look life-weary were her eyes, which were a startling blue. Two slices of sea glass resting in afternoon-lit sand.

“Sorry,” the woman said, looking at the delicate watch looped on her left wrist. “I am so late for the afternoon shift, and I’ve still got to get the baby up from his nap. If you’re interested in the apartment and don’t mind me shouting at you as I run around, come in.”

“We’re—” The women let the screen door slam shut behind her before Homer could continue. He turned around. Mia had drifted down the cracked walkway to the place where the sidewalk met the winter-brown front lawn. Her arms were wrapped around her stomach. She looked so alone, it made something catch in Homer’s chest. His breath felt studded with thorns.

“Mia.” Her name came out a whisper; it could not possibly reach her. Homer cleared his throat. “Mia.” Her hair lifted and fell in fruit-punch-red waves, but no other part of her moved.

The third time, Homer shouted her name, surprising himself with how scared he sounded. “Mia.” This time she turned. “She invited us in.” Homer gestured toward the door.

Mia’s arms hung by her sides like invisible cinder blocks were attached to her wrists as she made her way up the path. “Sure,” she said, ducking under Homer’s arm to go through the doorway. “Let’s.”

Homer followed her in, gently pulling the door shut behind him. He wanted to ask, “Where’s Dotts?” but he caught the words and turned them into a cough before he could. He wasn’t exactly sure why.

It took a moment for his eyes to adjust to the dim light. The door opened up right into a living room with a small flatscreen TV, a plaid love seat, and wall-to-wall carpeting littered with baby toys.

The woman with the shockingly blue eyes appeared in the doorway of the kitchen at the end of the hall. A baby, wearing only a diaper, rested on one of her hips, a waffle clutched in its two hands.

As she walked toward them, Homer saw that she had changed into an all-black outfit and pulled her hair into ponytail at the nape of her neck.

“Sorry about that. Goober here,” she said, touching her forehead against the baby’s, “is teething and doesn’t give his poor mommy a moment’s rest. Do you?” The pitch of her voice rose as she made cooing sounds. The baby pumped the waffle up and down, banging the woman on the nose and flinging crumbs on her face. “Motherhood is so glamorous,” she said, wiping her cheek against her shoulder. “But I guess you’ll find that out soon enough.” She jutted her chin toward Mia, who hadn’t moved far from the door. “When are you due?”

“February,” Mia croaked. “I call mine Tadpole.” Her voice made the barbs in Homer’s chest catch again.

“Good name. Goober’s daddy, piece of shit that he is, used to call him Guppy, but we changed that to Goober when Mommy kicked his ass to the curb. Didn’t we, sweetheart. We sure did.” The woman straightened up. “So I can’t let you see the space now. My brother’s repainting it and the fumes are terrible, but it’ll be ready at the end of the month. It’s just over the garage. It’s what you’d call cozy.” She looked Homer up and down. “You might have to duck in some places, but it has a good-size kitchen, window in the bathroom, and built-in closets. If you can survive living there with a newborn, you two will make it much longer than me and my ex.”

“Oh, we’re not,” Mia stammered. “Tadpole’s not Homer’s.”

“We’re not here about the apartment,” Homer said, just a beat after Mia. “Sorry. I’m—”

“You here for a cut? I don’t work out of the house anymore.” The woman dragged a bulging black purse from under a side table and starting sifting through it with the hand that wasn�

��t holding the baby. “I rent a booth at Orleans Beauty and Spa on East Main. Had to get out of the house or— Why can’t I ever find anything in here? There they are.” She dropped the purse and handed a business card to Homer, then another to Mia, who took the cardboard rectangle and held it listlessly in front of her, dangling it between two fingers. “Since you’re new customers, I can count one of you as a referral. Ten percent off.” The woman tilted her head as she studied Mia. “Can’t do much about your roots while you’re expecting. But a rinse might even out the color some until you can dye it again.”

“Trisha Moore. Licensed Esthetician.” Homer read out loud without knowing if he meant to. The connection between his head and the rest of him was scrambled, hazy. “Sorry. I . . . I think we got the wrong house. Do you know Dotts, I mean Dorothy Sampson?”

“You two her friends?” Trisha asked, but didn’t wait for an answer. “Wow. That girl did not tell anyone she was leaving, did she?” Trisha wiped waffle crumbs off her arm as she spoke. “I wish I could tell you some good news, but Dorothy ran out on a month’s rent three or so months ago. I haven’t seen her since. She seemed like a good kid who’d been knocked around by life and bad luck. I felt for her, you know.” Trisha kissed the top of the baby’s head.

Mia didn’t say anything, so neither did Homer. They must have looked disappointed, or maybe Trisha just felt compelled to fill the silence, because she added, “She, Dorothy, was doing real good for a while. I got her a job as a shampoo girl. She was going to school at night. All that.” Trisha swung her hips from side to side, cooing to Goober before adding, “Didn’t help that she was hooking up with a lowlife from Varney Beach. Whatever reason she ran off for, I bet that SOB’s behind it.”

Trisha looked at her watch. “Shit. I’m sorry, but I’ve got to go.” She scooped her purse off the floor and flung it over her left shoulder and smiled at them apologetically as she held the door for Mia, then Homer, before shutting and locking it.

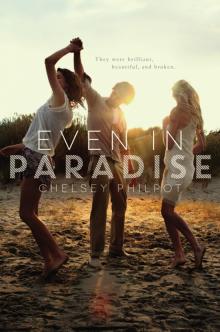

Even in Paradise

Even in Paradise Be Good Be Real Be Crazy

Be Good Be Real Be Crazy